Repression Investing: Got Gold?

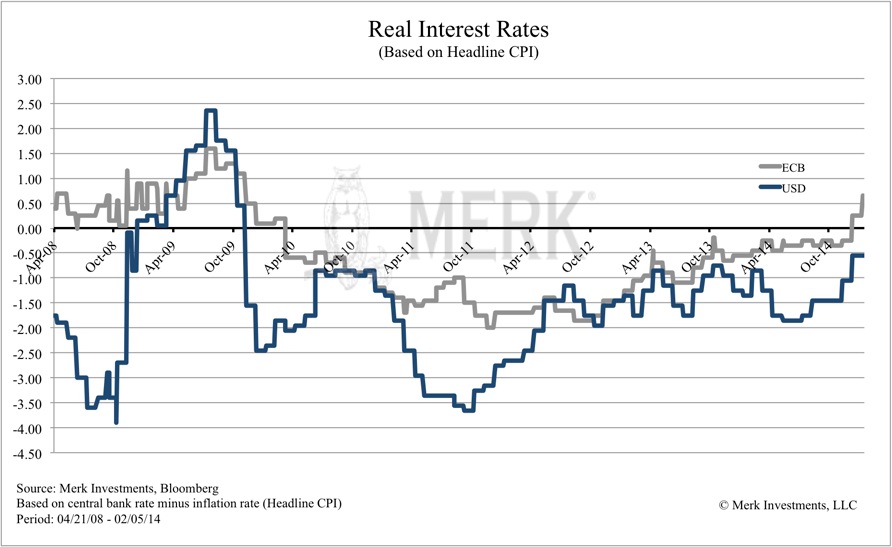

Axel Merk, Merk Investments February 11, 2015 Gone are the ZIRP days – the ‘Zero Interest Rate Policy’ is being replaced by negative interest rates in various countries. ZIRP is a form of financial repression, where savers earn less than the inflation rate to discourage saving. Pundits suggest the U.S. has chosen a different course, as ‘liftoff’ may soon take U.S. rates higher. We’ll try to separate reality from fiction, discussing investment implications for the U.S. dollar and gold. Much of investing is about trying to retain or enhance purchasing power. Even conservative investors are enticed to take risks, as hoarding dollar bills is an all but certain way to lose purchasing power when there is inflation. Real interest rates, i.e. nominal interest rates net of headline inflation, have been negative for some time, making holding cash a losing proposition. The chart below shows that when using the headline consumer price index as a reference point, financial repression has been rampant for some time. Below are real interest rates in the U.S. and Eurozone, i.e. nominal interest rates minus headline consumer price index (CPI) based inflation:

This chart shows:

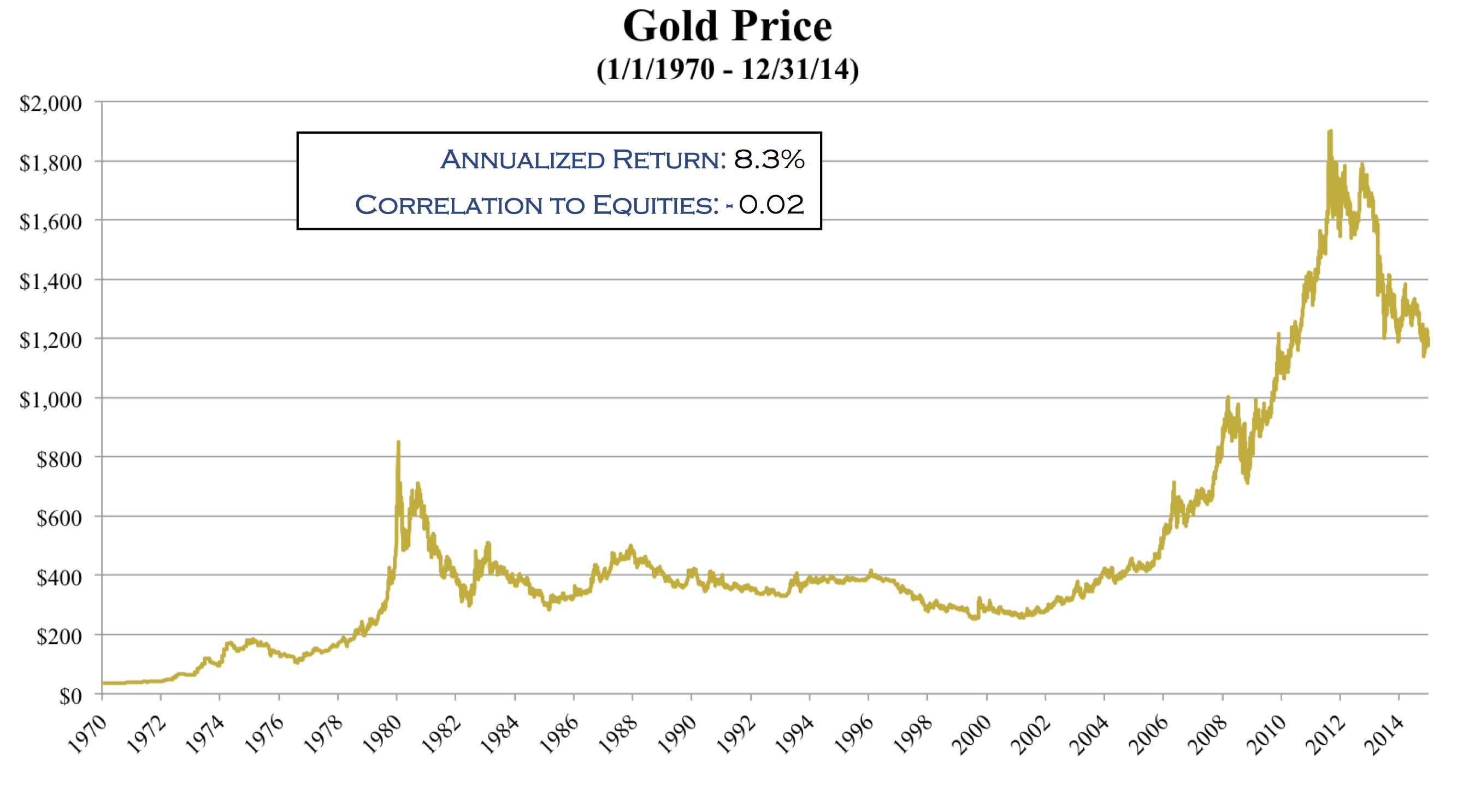

We wouldn’t want to talk anyone out of holding cash. However, investors need to be aware of what it is: in our assessment, when real interest rates are negative, cash cannot be considered “safe.” We have long warned that there may be no such thing as a safe asset anymore and investors may want to consider a diversified approach to something as mundane as cash. Let’s look at gold. Critics decry it as an unproductive, barbarous relic. It’s correct that this shiny metal doesn’t pay any interest and may be ‘unproductive.’ But we just saw that cash, another unproductive asset, yields negative real interest. Gold may be a formidable competitor when real interest rates are negative, i.e. in an era of financial repression. Now, clearly, the risk profile of gold is different from that of cash. Most have their daily expenses priced in their local currency rather than ounces of gold, making the value of cash more predictable for short-term expenses. A business can be valued based on various models taking future earnings into account (e.g. through a discounted free cash flow model). Similarly, when looking at gold, investors may want to consider what the future may bear. It’s not that the gold will change, but the currency in which it is valued: since 1970, the price of gold has had an average return of 8.3% per annum through the end of 2014:

If we chose to look at the past 100 years, we would also get attractive returns, although U.S. investors weren’t allowed to hold gold during part of that time. Most investors appreciate an 8.3% annual return; there are a couple of challenges, though:

It also turns out that the purchasing power of gold hasn’t changed all that much: a gallon of milk or a suit cost about as much in gold 100 years ago as they do today. This suggests:

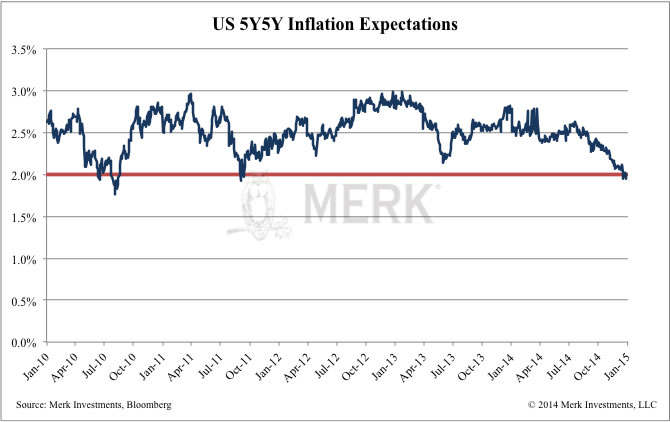

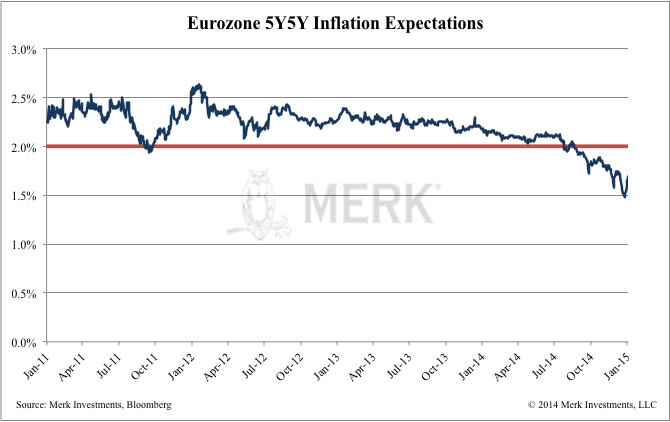

Let’s look at the crystal ball of what the future may bear. A valid criticism of the ‘real interest rate’ chart above is that it looks at current rather than future inflation. Central banks have various ways to gauge future inflation expectations. Without getting into technical details, the charts below, one for the U.S. and one for the Eurozone, are supposed to eliminate short-term noise, focusing on longer-term inflation expectations:

The red line refers to the 2% inflation target; central bankers get worried when expectations of longer run inflation are at risk of falling ‘too low.’ That’s why European Central Bank head Draghi is ringing the alarm bell. In the U.S., Bernanke historically announced another round of QE when the above chart approached 2%. So while the ECB turns on the printing press, the Fed, looking at similar trends, shrugs them off, blaming low oil prices for distortions in this way of looking at the data. Never mind that this way of looking at the data is supposed to filter out the short-term effects of oil. We draw from this: First, central bankers are prone to interpret the data to serve their agenda. We can make lots of arguments why QE in the Eurozone is inappropriate; and, conversely, the Fed appears to engage in a make believe assessment of the economy. The future policy course may increasingly be driven by ideology. With interest rates low, we have our doubts real interest rates are going to move high anytime soon. In the context of this discussion, it is high real interest rates that pose a threat to the price of gold. Let’s look at another forward-looking measure: the Congressional Budget Office’s (CBO’s) outlook on deficits. No, this isn’t about the budget proposal projecting deficits over the next decade, but the most recent CBO outlook projecting long-term deficits:

Many criticize CBO numbers as being notoriously inaccurate. Maybe. But in our analysis, in a decade from now, the U.S. may be paying $1 trillion more a year in interest expense alone should the average cost of borrowing go back up to its historic levels. There may not be money for other government programs left; one way of looking at the challenge is that the biggest threat to national security may be the deficit because there may not be any money left for the defense budget. Let’s not scoff at Greece and Europe: the U.S. has related challenges. To us, this avalanche of expenses may provide an incentive to keeping real interest rates low to help the government finance itself. Indeed, we think it may be difficult to have positive real interest rates for an extended period of time over the next decade. I would like to caution that when I explained my concern to a Fed policy maker, he said this outlook is unrealistic as it wouldn’t provide a stable equilibrium. My response: I never suggested this would be stable. We can avoid the explosion of deficits with major entitlement reform. We could introduce means testing to receive benefits; we could increase the age at which social security gets paid. There are solutions to these problems, but they are politically very difficult to implement, no matter who controls Congress. The Europeans have tried austerity. In the U.S, we may favor the magic wand of the Fed. Having said that, many U.S. benefits are indexed to inflation, causing the printing press to be of little relief unless unless the CPI under-states inflation. Another way to look at this is that this is the first time in U.S. history that both the government and consumers have what we believe is too much debt. Foreigners – that don’t vote – own much of this debt. This provides an incentive to debase the value of the debt. Differently said: interests of the government and savers are not aligned. More broadly speaking, investors – be that in the U.S., Japan, Europe, can’t rely on their government to preserve the purchasing power of their savings. We don’t need to be right about the future. As long as there’s a risk that we are right, it may be prudent to take it into account in an asset allocation. If you like to learn more how to construct a portfolio in an era of financial repression, and what role gold may play in such a portfolio, please register to join us for our February gold webinar. If you believe this analysis might be of value to your friends, please share it with them. Also, if you haven’t done so, please sign up to receive Merk Insights for free.

Axel Merk Axel Merk is President & CIO of Merk Investments  Follow @AxelMerk Tweet Follow @AxelMerk Tweet

|