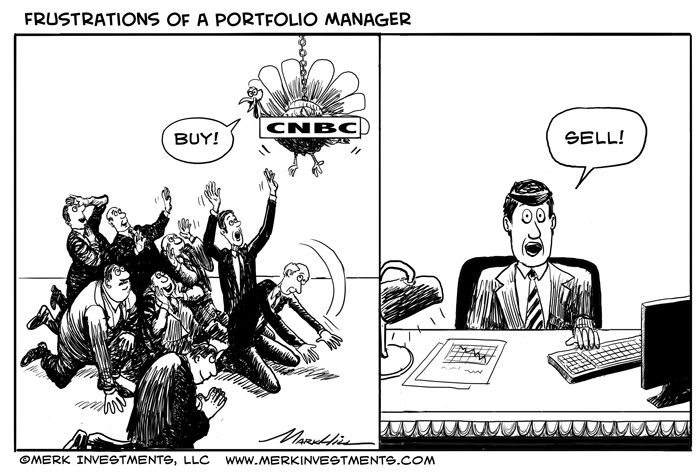

Frustrations of a Portfolio Manager: Why I Sell the Dollar

Axel Merk, Merk Investments July 17th, 2013 Markets are meant to exert the maximum amount of frustration on investors; indeed, the markets have lived up to their side of the bargain. To survive and possibly thrive in the business, portfolio managers need to be a special breed. This newsletter is a bit different from our typical analysis in that I provide insight as to how I approach the markets, what makes me get up in the morning, and how you can get the most out of your portfolio manager.

I have been investing since the early 1980s; when I was a kid. The "markets" have always surrounded me as my dad was in the business. Not only was he in the business, in my eyes, he was right up there with the most successful investors of all times, even without a public profile. Like other successful investors, for him, the world was always black and white. Buy or sell. Or let me rephrase: buy big or sell big. I remember, in the early 1980s, CEOs of high tech companies visiting our home in Switzerland to solicit his support to raise money. One of these firms is still around doing well. In contrast, I recall the weekend tension when another CEO was ousted by its board; the following Monday the Nasdaq had its largest block trade ever up to that time, courtesy of my dad exiting his clients' positions. He and his clients took a hit that day, but had multiplied their money many times in the preceding years in that stock. A few years later that firm filed for bankruptcy. Later, during the October 1987 crash, my dad faced an ethical dilemma of different sorts: should he order champagne because he was dramatically short the markets or should he show restraint, in sympathy with others? I recall picking up the phone at home when a large client of his called – it was the one and only client of his that had explicitly told him not to hedge his portfolio; after the crash that client changed his mind. Managing other people’s money, one doesn’t just face volatile markets. The portfolio manager may need to be a therapist of sorts; holding clients’ hands, managing expectations and providing direction. In larger firms, the portfolio manager is often shielded from client facing roles but in smaller firms the relationship manager and asset allocator or portfolio manager are often one and the same. Investors are diverse. Some are always happy, some nag, some are engaged and others are removed. As this industry is built on trust, a common type of client is the type that claps the adviser’s shoulder and says, “I trust you’ll take care of me.” Some clients live up to their end of the bargain, saving diligently; others spend lavishly, save too little, but still expect their investment adviser will plan their retirement. My personal experience suggests that there is frequently an inverse relationship between income and how much money is put aside for retirement. I started managing client money in college. I was young and hungry for ways to “beat the markets,” taking graduate level seminars early on. A friend of mine and I won a prize for a paper we wrote as undergraduates on “noise” in the futures markets. Aside from an undergraduate business economics degree, I also earned a Master’s degree in computer science; both from Brown University. The Ivy League school is best known for allowing their students to build their own curriculum. And I did. But rather than combining African drumming with archeology, I had a razor focus on combining financial research with artificial intelligence. Together with a colleague, we petitioned the President of the University to make what may be the most flexible curriculum in the nation even more flexible – not to make the program easier, but allow an even more comprehensive and long-term focus on an area of study. I looked at everything from neural networks to genetic algorithms to develop models to “beat the market.” My Master’s thesis was on a “Probabilistic Decision Support System” – notably, the work focused not only on forecasting prices but also volatility and liquidity. This was long before a now famous intellectual wrote a book about Black Swans warning about vaporizing liquidity and surging volatility. I went on to London to work on a Ph.D. at Imperial College, the “MIT” of London; there, operations research and game theory provided much of the framework but ultimately my enthusiasm for the markets continued to drive me. Like many sons, I revolted a bit against stepping into my dad’s footsteps, although to the casual observer that may not be apparent. That black and white thing wasn’t for me: to me, the world was always shades of grey; anybody who has a faint idea of what a “probabilistic decision support system” might be will understand what I mean. I have always looked at the world in terms of scenarios, and then assigned different probabilities to them. In plain English, my investments have always been focused on what I believed were prudent risks (those my clients and I can sleep with at night). Mind you, I am also a computer scientist at heart. That’s relevant because, for a computer scientist, a bug in a program causes it to crash. Or, translated to the markets, I take Black Swans, those boundary conditions, extremely seriously. In fact, I got more than a little frustrated in reading academic papers in finance as one after the other appeared to simplify those boundary conditions away. I eventually dropped out of the Ph.D. program to launch Merk Investments in 1994. I started an offshore hedge fund mostly because it appeared to be the most straightforward way to build a track record. By then I had learned a thing or two about he markets, foremost, possibly, that the more I dived into modeling, the more I learned about deficiencies of modeling. Systematic (rule based, or “quant”-driven) investment strategies might sell well (i.e. attract client money) but tend to work better on the drawing board than in practice. It’s always been a challenge but even more so since the financial crisis: when policy makers are actively engaged in the markets, no matter how good one’s back-testing, a model driven investment approach is likely to have its set of challenges. Not surprisingly, over the years, we got further and further away from modeling, increasingly pursuing a “discretionary macro” investment approach. In a discretionary macro approach which is a fancy way of saying one invests according to one’s conviction, one needs to make sure one is not merely randomly throwing darts. Our framework is monetary policy. And while we are not stubborn, I believe we have shown over the years a consistent framework that has frequently allowed us to be a step ahead of the market, such as when the credit bubble was building (please read past editions of Merk Insights that we started sharing with the public as of 2003). While my accent may “qualify” me to talk dollar, currencies & gold, I actually started out investing in high tech companies. The one consistent theme throughout my investment career has been to focus on correlations and volatility across assets and asset classes. The best bubble indicator, in my view, is when correlations break down (think tech stocks all moving up in tandem); or volatility is abnormally low (the goldilocks economy through parts of last decade, Treasury bonds proving an eerie feeling of ‘safety’ masking potentially severe interest rate risk). As such, in the middle of the 1990s, my firm started diversifying beyond tech stocks; in the late 1990s we began to invest more globally. Then around 2000 we accelerated our shift to a macro approach of investing. As we were increasingly concerned about the markets, we increasingly managed cash, international cash and precious metals. And that’s how we drifted into the realm of hard currencies. It’s in recent years that we added more quantitative analysis, again, keenly aware of its limitations, but also cognizant of potential benefits. Having moved the business to the U.S. in 2001, we were faced with the same challenges as many others, specifically, decreasing profit margins of our advisory business as our strategies became more conservative just as regulatory overhead was going up. Rather than do what many in our industry did; merge with another adviser; we opted to invest into what we deemed a more scalable business model. In 2005 we launched our first mutual fund. The mutual fund industry is a high fixed cost business. We were told it was suicide to enter a saturated industry. And while we are not allowed to give many guarantees in our business, I can assure anyone starting out in the mutual fund business; especially when seeding the first mutual fund with only $1 million in assets (we did not deploy client assets into the first fund); you have the best incentive of all to grow the business. We sold some real estate (we were a tad early in identifying the real estate bubble, but thought there’s better use for the money) to invest into our business. The rest is history and we now manage four mutual funds; all with a focus on currencies. Although there is more to it: throughout my investment career, I generally have put my money where my mouth is, typically investing alongside clients. To date, I cannot warm up to the Wall Street mantra of “independence” where analysts proudly exclaim that they have no stake in the opinions they write, other than a potential bonus at the end of the year based on hypothetical data points. In contrast, my approach is open to the criticism of “talking my book,” but those that think so have it backwards: when we have offered investment services, it’s because we believe they may help investors navigate the markets. One reason we went into the mutual fund business was related to what I mentioned earlier: while I enjoy client interaction, what always attracted me to the mutual fund business is the “take it or leave it” characteristic. A mutual fund firm offers funds with specific objectives. It’s our job to follow the investment process outlined in the prospectus and to do our best at meeting the objective. Investors that deem a fund appropriate for them may invest. If they don’t like the fund anymore they can sell any day. As such, while I spend a lot of time talking with investors, we service about 40,000 investors these days. Very different from the dozens of investors our old business model used to serve. Indeed, we phased out what we call our “legacy business.” One thing I learned early on was that building a track record alone does not attract clients. A good product is one thing but one needs to be able to communicate. Foremost, having my performance published in databases in my early years earned me sales calls from brokers trying to sell me something. I learned that an investment product needs to be simple enough so that one can explain the investment process. Seems easy enough. In the extreme, there’s a reason index funds are so popular. But I also learned another interesting lesson: as we phased out our legacy business a lot of clients begged us to keep them on. Not only did many beg us to keep them, many offered to give us more money to manage if we only kept the separate accounts business. It was flattering feedback but as our mutual fund business was growing we were determined to be focused; we closed all separate accounts and other investment products we managed. Some of you may wonder at times how we publish so much. First of all, I have a great team supporting me. While I write many "Insights" myself, I tend to be only one of the collaborators on our white papers. A couple of years ago, at the urging of our readers, I started to have my writings edited for proper English; I can only imagine how much smarter I must look these days! What about the cartoons? We love them as much as you do: coming up with a theme for them is fun. At times our marketing manager comes up with an idea after we decide on the topic for the next newsletter; sometimes I give close guidance; always, the cartoonist we contract with, Mark Hill, brings a smile to our faces. But ultimately there's one secret, that isn't a secret at all, as to why we publish so much: we are passionate. Just as others are passionate about football, we are passionate about the dollar. More importantly, I am furious as to where policymakers throughout the world are taking their respective countries. In my view, monetary policy has a greater impact on wealth distribution than fiscal policy does. Never mind Republicans or Democrats, it's the Fed that controls the money. So when I write a newsletter, it's usually because I got ticked off by something. The catalyst that prompted me to be more public with my views was in 2003 when the head of the European Central Bank said, "We hope and pray that the global adjustment process will be slow and gradual." For those not familiar with central bank talk, the "global adjustment process" is a code word for a dollar crash. More importantly, seeing central bankers revert to hopes and prayers made me think, “I need to do something!”. This led to the re-engineering of our business and set us on the path we are on today. Investing is not a precise science: just because your analysis shows a security (or currency, or gold) is under-valued, doesn’t mean the rest of the world agrees. That discrepancy can last for a long time. I gather most investors would agree to the saying that “markets may remain irrational longer than you can stay solvent.” When our investment approach leads to valuations different from those reflected in the market we first try to understand why there’s a discrepancy. If we think the market’s view might converge with ours, then there’s a potential opportunity to profit. Applied many times over, it may lead to above average returns. Here, too, though, there’s more to the theory: just as I get sufficiently ticked off by moves of policy makers to write newsletters, I have visions of the world unfolding – not in terms of security pricing models but in terms of socio-economic implications of policy actions, in terms of the road different nations are traveling on and what it may mean for the sort of decisions that ultimately affect, you guessed it, currencies and the price of gold. And while I admire economists that get satisfaction predicting GDP growth to the 2nd decimal place, I am troubled by policies that are blatantly destroying wealth the social fabric, increasing the wealth gap, hindering economic growth, and providing fertile growth for populism and destruction. To put a brave face on it, I position a portfolio to mitigate the impact, or possibly profit from such policies to the extent that I believe my visions in the context of a broader analysis have a non-negligible chance of becoming reality. Cutting out the convoluted talk: I’m concerned about monetary policy the world all over and I’m concerned because I believe my team does a formidable job in researching central bank policies. And then of course there’s fiscal and regulatory policy but those come in second and third in assessing global dynamics. The industry continues to evolve as do we, yet I am not permitted to write about the exciting things we are working on. But managing mutual funds does not isolate one from investor psychology. There’s an old saying that retail investors are dumb, while professional investors are smart. I have always disagreed; showing great respect for all of our investors. Retail investors are tremendously educated. Still, it is the nature of our investment process to be at odds with prevailing market opinions. And we like it that way because we fear we might be buying something overpriced when too many others agree with us. Conversely, of course, it can be frustrating, as a mutual fund setting makes it more difficult to conduct that dialogue as to why one holds a contrarian view. Sometimes I dream of the days when we phased out that legacy business and imagine calling an investor, whose investment decision I disagree with, urging them to take all their money out. I wonder whether their response would be to increase their investment with us instead? This leads me to the question: How we can serve investors? We must not promote our mutual funds in this setting, and this should not be construed as a solicitation. However, we have the infrastructure these days to go full circle, e.g. to offer separate accounts or even a hedge fund again or act as a sub-adviser on behalf of others. Tell us how we can serve you. What type of services would you like us to offer? Let us know; email us. If our cartoons are all you are interested in, then let us know that too. By engaging us, you provide us with valuable feedback. Importantly, please make sure you are subscribed to our newsletter so you know when the next Merk Insight becomes available. Upcoming is an analysis of implications of the “untapering” at the Federal Reserve and in a separate analysis we will discuss the aftermath of Japan’s Upper House elections with implications for the yen. Also, please join us for our upcoming webinars that discuss gold or the currency asset class in more detail: click to join our webinar list ; our next Webinar is Thursday, July 18. Axel Merk

|